Threatened species don’t just live in national parks

Private landholders hold the key to retaining biodiversity

Environmental research across Australia underlies this commentary and analysis by Stephen Kearney, The University of Queensland; April Reside, The University of Queensland; James Watson, The University of Queensland; Rebecca Louise Nelson, The University of Melbourne; Rebecca Spindler, UNSW Sydney, and Vanessa Adams, University of Tasmania

OVER THE LAST decade, the area protected for nature in Australia has shot up by almost half. Our national reserve system now covers 20% of the country.

That’s a positive step for the thousands of species teetering on the edge of extinction. But it’s only a step.

What we desperately need to help these species fully recover is to protect them across their range. And that means we have to get better at protecting them on private land.

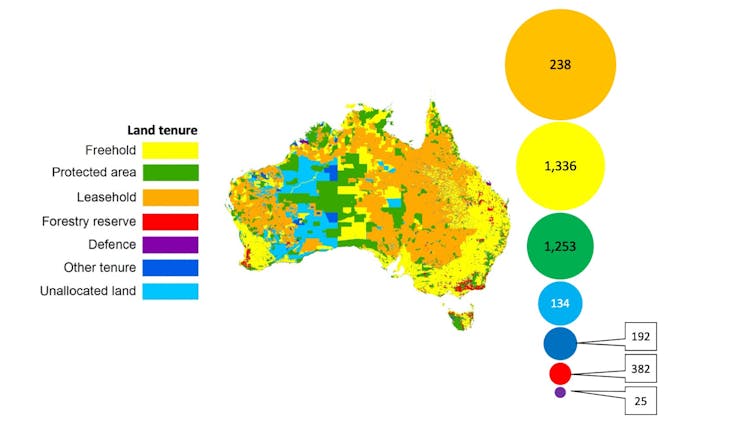

Our recent research shows this clearly. We found almost half (48%) of all of our threatened species’ distributions occur on private freehold land, even though only 29% of Australia is owned in this way.

ABOVE: Glenn Jenkinson, Dreamstime.

By contrast, leasehold land — largely inland cattle grazing properties — covers a whopping 38% of the continent but overlaps with only 6% of threatened species’ distributions. And in our protected reserves? An average of 35% of species’ distribution.

Why do we need more? Aren’t our protected areas enough?

When most of us think of saving species, we think of national parks and other safe refuges.

This is the best known strategy, and efforts to expand our network are laudable. New additions include the Narriearra Caryapundy Swamp National Park in northwest New South Wales, Dryandra Woodland National Park in Western Australia, and several Indigenous Protected Areas around Australia, which will ensure greater protection for some species.

But relying on reserves is simply not enough. From the air, Australia is a patchwork quilt of farms, suburbs and fragmented forests. For many species, it has become difficult to find food sources and mates.

Since European colonisation began, we have lost at least 100 species, including three species since 2009.

Almost 2,000 plant and animal species are threatened with extinction, with dozens of reptile, frog, butterfly, fish and bird and mammal species set to be lost forever without a step change in resourcing and conservation effort.

What we do on our properties matters to nature

Freehold land is home to almost half our threatened species. Species like the pygmy blue-tongue lizard (Tiliqua adelaidensis) and giant Gippsland earthworm (Megascolides australis) occur almost entirely on privately owned lands.

By contrast, leasehold land overlaps with only 6% of species’ distributions. Though that might sound low, species like the highly photogenic Carpentarian rock-rat (Zyzomys palatalis) rely entirely on leased land.

What about the 1.4% of Australia set aside for logging in state forests? These, too, provide the main habitat for threatened species such as Simson’s stag beetle (Hoplogonus simsoni), which has over two-thirds of its distribution in state forests in Tasmania’s northwest. Similarly, the Colquhoun Grevillea (Grevillea celata) is known only from a state forest in Victoria’s Gippsland region.

Even defence lands — covering less than 1% of Australia — are the only home some species have. Take the Cape Range remipede (Kumonga exleyi), known only from an air force bombing range near Exmouth, Western Australia, or the Byfield Matchstick shrub (Comesperma oblongatum), which survives in Queensland’s highly biodiverse Shoalwater Bay Military Training Area.

The Indigenous estate across Australia intersects with almost all of these tenure types, and also has critical importance for half of Australian threatened species distributions as shown by previous research.

We need all hands on deck to keep our threatened species persisting

It is late in the day to save Australia’s threatened species, as climate change multiplies the challenges they face. If we are to have any real chance at turning the tide, we must do much more.

To staunch the heartbreaking flow of species into extinction means we have to actively manage multiple threats to their existence across many different types of land tenure.

Logging of native forest and some methods of intensive farming continue to endanger many threatened species, particularly those which rely on these land types for their survival.

Over 380 threatened species have part of their range in land set aside for logging. It should be no surprise that logging is a key threat for 64 of these endangered species.

How can we achieve better conservation outside protected areas?

Many landholders are acutely aware of the species they share the land with, and are already taking action to protect them. One key method is the use of land partnerships, in which landowners and custodians work with conservationists.

Take Sue and Tom Shephard, who run a large cattle property on Cape York. Their station is home to some of the last remaining golden-shouldered parrots (Psephotus chrysopterygius). The Shephards are working to bring the species back from the brink through careful management of grazing, fire and feral animals.

Similarly, the work of hundreds of rice growers is helping save the endangered Australian bittern (Botaurus poiciloptilus). Every year, up to a third of the remaining population descends on New South Wales rice fields to breed. Rice farmers are accommodating these birds by ensuring there is early permanent water, reducing predator numbers and boosting their habitat.

We’re seeing successes even on defence force land. The Yampi Sound Training Area in the Kimberley is a biodiversity hotspot. A partnership between the Department of Defence and the Australian Wildlife Conservancy is helping protect these species alongside defence force use. This model could be rolled out across other areas of defence land.

What’s stopping more people taking action?

While many landowners may want to help, financial constraints, a lack of knowledge or concerns over implications for resale of the land can be barriers.

If we want to encourage more landowners to directly conserve species on their land, we must begin by understanding what they want. Only then can we design initiatives to help these species, as well as benefit and engage landowners.

What does this look like? Picture financial incentives to join conservation programs. Or workshops where landowners can see the very real benefit to their own land by reducing erosion, keeping rabbit numbers under control, protecting waterways from silt or water-sucking introduced trees, or reducing wind and dust through setting aside land for trees.

If a farmer or landowner can clearly see the benefit for wildlife and for their own use, they are much more likely to take part.

Incentives don’t have to be financially based, either. If landowners understand what works and feel capable of action after training, and have technical support and assistance to draw on, they’re more likely to start down the path of making their land more friendly to threatened species.

If we really want to protect our species, we must do more to bring in Australia’s farmers, landowners and other custodians of land. We cannot rely on protected areas alone. We need to make the land safer for our species most at risk, wherever they occur.

CSIRO’s Josie Carwardine and Anthea Coggan contributed to this research.

Stephen Kearney, PhD student, The University of Queensland; April Reside, Lecturer, The University of Queensland; James Watson, Professor, The University of Queensland; Rebecca Louise Nelson, Associate Professor in Law, The University of Melbourne; Rebecca Spindler, Adjunct Professor, UNSW Sydney, and Vanessa Adams, Senior Lecturer, Discipline of Geography and Spatial Sciences, University of Tasmania

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Yet, the federal environment minister

Yet, the federal environment minister