Charles Darwin’s finches on the brink of extinction

The birds naturalist Charles Darwin saw on the Galapagos Islands during his famous voyage around the world in 1831-1836 changed his thinking about the origin of new species and, eventually, that of the world’s biologists.

On his visit to the Galapagos Islands, Darwin discovered several species of finches that varied from island to island, which helped him to develop his theory of natural selection.

The 13 major islands of the Galapagos are home to an amazing array of unique animal species: giant tortoises, iguanas, fur seals, sea lions, sharks, rays, and 26 species of native birds––14 of which make up the group known as Darwin’s finches.

It was Darwin’s job to study the local flora and fauna, collecting samples and making observations he could take back to Europe with him of such a diverse and tropical location.

The research performed there and the species Darwin brought back to England were instrumental in the formation of a core part of the original theory of evolution and Darwin’s ideas on natural selection which he published in his first book On the Origin of Species.

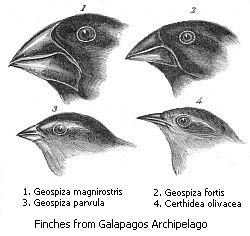

Their beaks had adapted to the type of food they ate in order to fill different niches on the Galapagos Islands.

Wide, slender, pointed, blunt: The many flavors of beak sported by the finches that flit about the remote Galápagos Islands were an important clue to Darwin that species might change their traits over time, adapting to new environments. The Galápagos finches are ideal subjects for observing the drama of evolution. The islands kept them isolated from competition with other birds on the South American mainland, and each island became its own little world.

But Darwin failed to note which islands each particular finch came from. He tried to make up for the deficit by borrowing some finch notes taken by the Beagle‘s Captain Robert FitzRoy, but Darwin hardly mentioned the finches in his later writing. It was not until Darwin’s Finches were properly identified and studied by the famous ornithologist, John Gould, that Darwin began to realize that a more complex process was going on. Some developed stronger bills for cracking nuts, others finer beaks for picking insects out of trees, one species even evolving to use a twig held in the beak to probe for insects in rotten wood. Each small adaptation gave a competitive advantage and so the characteristic spread through the population.

Darwin himself used the finches in the The Voyage of the Beagle to quietly announce the theory of evolution.

“Seeing this gradation and diversity of structure in one small, intimately related group of birds, one might really fancy that from an original paucity of birds in this archipelago, one species had been taken and modified for different ends.”

(image: Small Ground Finch Geospiza fuliginosa, from the island of Santa Cruz, Galapagos Islands.)

Parasitic flies could wipe out the Galapagos Island birds in just 50 years.

An estimated 270,000 medium ground finches live on the island of Santa Cruz, and it is thought 500,000 live throughout the archipelago. Researchers were able to document how the flies have damaged finch reproduction between 2008 and 2013. The fly, known by the scientific name Philornis downsi, lays its eggs in finches’ nests. The flies lay their eggs inside the birds’ nests, and the hatching maggots feed on the young birds.

A frog named for Darwin has already gone extinct!

However, the researchers also found the problem could be solved by more advanced and widespread pest-control efforts. Using insecticides, including placing pesticide-treated cotton balls where birds can collect them to self-fumigate their nests, may be used to counteract the parasites.

The threat the finches face as a result of the invasive flies illustrates how “introduced pathogens and other parasites pose a major threat to global diversity,” especially on islands, which tend to have smaller habitat sizes and lower genetic diversity, researchers write.

Surely, we can do something for the very birds that the famous Charles Darwin studied, in a protected and isolated highly conserved and protected archipelago?