LONELY AT THE TOP: Meddling in Ecosystems

By Natalie Kyriacou

About the author:

Natalie Kyriacou is the Director of My Green World, an organisation dedicated to the conservation and protection of wildlife and habitats. She has worked on various animal welfare and conservation projects, including an orangutan rehabilitation program in Borneo, an elephant rescue program in Sri Lanka, and a dog sterilisation clinic in Sri Lanka and Australia.

Natalie holds a degree in Journalism and a Masters in International Relations at the University of Melbourne. She is a current appointed member of the Animal Ethics Committee for the Department of Veterinary Sciences at the University of Melbourne.

ORIGINS OF THE DINGO

With somewhat murky ancestral origins and a much maligned reputation in Australia, the dingo has long been considered a polarizing predator; both a cultural icon and livestock pest.

Perhaps no other predator is more deeply embedded in the Australian psyche than the dingo. Its history in Australia has grabbed headlines for more than a century, from the stolen baby in the infamous Azaria Chamberlain case to being the cause for the construction of the legendary Dingo Fence in 1885 to protect grazing lands, the dingo has entrenched itself deeply into the rich fabric of Australian culture.

Bearing a striking resemblance to the domestic dog, the dingo is currently listed as a subspecies of the grey wolf, though its exact ancestry is highly enigmatic and much debated. More recent research suggests that the dingo came to Australia via Southern China, anywhere between 4600 and 18,300 years ago.

Despite its flawed reputation, Australia’s largest terrestrial predator is also a vital component of healthy ecosystems in Australia and an important contributor to environmental recovery and the protection of threatened native species.

HAUNTING CONSERVATIONISTS

Considered one of the most vexing issues facing conservationists and agriculturalists alike, the dingo has haunted the Australian landscape for over 200 years.

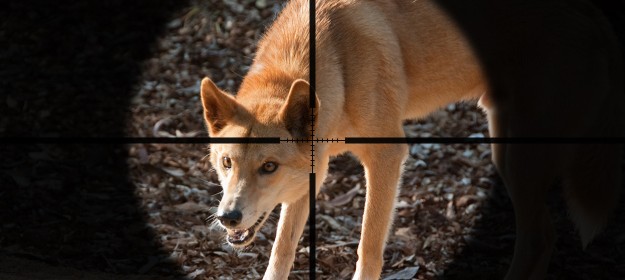

The culling of dingoes is commonplace in Australia, and their numbers have fluctuated widely as a result. Government-run programs consenting the dingo cull are active across the country, with methods including poisoning, shooting and using sodium fluoroacetate.

The deadly drama of predators and their prey is often described as a prime example of natural selection in action, however, often overlooked is the role that humans play in these relationships, and how their meddlesome actions within precious ecosystems can have devastating consequences.

THE APEX PREDATOR

Most recently, the dingo has experienced catastrophic decline as a result of human persecution. Such a collapse of top predator populations is associated with dramatic upsurges of smaller predators. Known as the mesopredator theory, this trophic interaction has been witnessed heavily in Australia. Disruption to the number of dingoes has a cascading effect throughout entire ecosystems, initiating a surge of unchecked predation by lower species and an unravelling of bionetworks.

When dingo populations dwindle, foxes, feral cats, and kangaroos grow bolder. Foxes and cats eat large quantities of small mammals, while kangaroos destroy vegetation which smaller marsupials live in, leading to an equally controversial kangaroo cull.

Thus, the crucial role of the apex predator is undermined frequently. The story of the dingo is not unique. The apex predator has been continually persecuted throughout the world, and the results are almost always the same.

ECOLOGICAL IMPACT

The impact that unregulated mesopredators have on ecosystems is something which has only recently been recognised. In 2006, scientists from James Cook University and Australian National University published a report in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B, tracking the geographical relationship between dingoes, threatened species, and now-extinct species.

Their research suggests that dingoes actually aid the survival of smaller, more vulnerable species in Australia, and their presence is actually associated with the persistence of native Australian animals. By suppressing populations of introduced predators and larger herbivores, the dingo actually reduced the threat to native species. The study found that in areas where dingoes had been removed, most of the native mammal extinctions had occurred.

WAR ON DINGOES

This complex ecological dynamic has been largely overlooked in Australia, and the war on dingoes has continued to rage, compromising their genetic strain, causing many dingo subspecies to fall extinct, and dooming much of Australia’s biodiversity.

If the dingo was entirely eliminated from Australia, then prey species would doubtlessly suffer. The dingo is not only a keystone species protecting mammal biodiversity in Australia, but it is the most significant constraint on the harmful potential of exotic predators. The notion that we must so thoroughly regulate and intervene in the wild is highly alarming, and the devastating impact it has on natural ecosystems is already being felt around the world.

Natalie Kyriacou

http://www.mygreenworld.org/war-on-dingoes/

Featured image: “Dingo Perth Zoo SMC Sept 2005”. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons