Our extinct Macropods – gone forever

Six species of macropod are already extinct and a number of species listed as endangered or threatened. European settlement of Australia has worked against the survival of many native animals, including some species of kangaroo, in four main ways: fire patterns have changed, domestic stock have grazed large areas of native habitat, new predators have been introduced, and land has been cleared. Seven are endangered, and about 18 are vulnerable for near threatened.

Seventy-six macropod species are listed, or in the process of being listed, on the IUCN red-list. A total of forty-two of these species, or more than 50 per cent, are listed as threatened at some level.

The Desert Rat-kangaroo –

has not been seen since 1935 and is considered extinct. They were found only in Australia in ranges that have been much reduced by colonisation and the introduction of European farming practices, especially sheep grazing.

(image: John Gould, and H C Richter, lithograph)

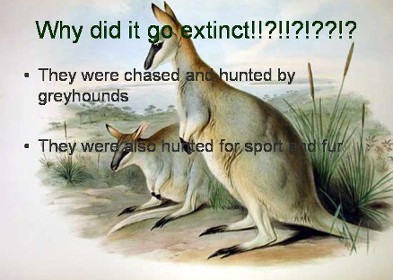

Toolache Wallaby

The species tend to rest in woodlands and then graze at night in adjacent grasslands or grassy patches in the forest.

(image: http://tatumcoachallen.pbworks.com/w/page/23008949/keeney%20Toolache%20Wallaby)

By 1910, populations had been reduced to a number of scattered colonies in the area enclosed by Robe, Kingston, and Beachport on the South Australian coast, and Naracoorte and Penola further to the east, near Mt Gambier. By 1924 only one small group was known to survive on Konetta Station, about halfway between Robe and Penola. An attempt was made to transfer some of the population to a sanctuary on Kangaroo Island, but this failed. The last known survivor died in captivity in Robe in 1939 (Flannery 1990d).

Although the Toolache Wallaby was hunted for its beautiful pelt and for sport, the biggest factor in its decline was the extensive opening up of its habitat that resulted from the drainage and clearing of native vegetation.

Hare-Wallabies

Hare-wallabies look a bit like European Hares. This group has severely declined with three of the eight or 38 per cent of the hare wallabies extinct and the remaining five all threatened or near threatened.

They also have the European Hare’s habit of hiding in tufts of grass. There are five known species of hare-wallabies. Of these, the Eastern Hare-wallaby (Lagorchestes leporides) is already extinct, and the Central Hare-wallaby (Lagorchestes asomatus) possibly so. Only one species, the Spectacled Hare-wallaby (Lagorchestes conspicillatus) is still widespread. Hare-wallabies mostly prefer tropical plains and grassland.

(image: Eastern Hare Wallaby John Gould and H C Richter, lithograph)

Crescent Nail-tail Wallaby

These wallabies are so named because of the horny spur they have at the end of their tails. There are three species of nail-tail wallabies. The Crescent Nailtail Wallaby (O. lunata) is extinct.

(image: By John Gould – John Gould, F.R.S., Mammals of Australia, Vol. II Plate 55, London)

This species was likely extirpated by predation from introduced foxes and cats. Habitat degradation, including changing fire regimes and the impact of rabbits and introduced stock, may have had an impact. In part of their range (south-western Western Australia and parts of New South Wales), pastoral expansion were likely to have been detrimental to the species.

Bettongs

The introduction of the red fox and European rabbit to Australia led to the extinction of the mainland subspecies of Eastern Bettongs during the 1920s. The Tasmanian (or Eastern Bettong) was once present in both Tasmania and from South Australia to Queensland but is now extinct on mainland Australia.

Potoroos

Gilbert’s Potoroo was thought to be extinct since the early 1900s. Then in 1994 they were rediscovered at Two Peoples Bay Nature Reserve near Albany, Western Australia.

The Broad-faced Potoroo (extinct) was collected from the Western Australian wheatbelt and east of Albany. Fossil evidence suggests it was once distributed throughout much of semi-arid south-western Western Australia and coastal South Australia. It was apparently extinct well before foxes arrived in Western Australia and before widespread land clearing. Its disappearance may have been due to predation by feral cats.

(image: )

Lesser Bilby

The Lesser bilby (macrotis leucura), also known as the yallara, the lesser rabbit-eared bandicoot, or the white-tailed rabbit-eared bandicoot. Trappers, predators, including the Aboriginal population, and territorial competition from rabbits forced the lesser bilby into extinction before it could be fully studied.

Recorded as a living animal on just a handful occasions between its discovery in 1887 and its extinction in the 1950s. Unlike the gentle and still surviving common bilby, it had a nasty temperament. It was said to be ‘fierce and intractable, and repulsed the most tactful attempts to handle them by repeated”. Distribution: Central Australia. Last Record: 1950s.

European settlement of Australia, and the exotic predators and herbivores they brought with them, caused rapid widespread biodiversity loss. As a result, for the past 200 years Australia has had the highest mammal extinction rate in the world.